The following program is from my Master’s degree recital from NYU Steinhardt, streamed lived on May 2nd, 2020.

Program

Piano Sonata in D Major, Op. 28

I. Allegro

II. Andante

III. Scherzo et Trio: Allegro vivace

IV. Rondo: Allegro non troppo

(approximately 20 minutes)

Two Concert Études, S. 145

I. Waldesrauschen (Forest Murmurs)

II. Gnomenreigen (Dance of the Gnomes)

(approximately 15 minutes)

Valses nobles et sentimentales

I. Modéré, très franc

II. Assez lent, avec une expression intense

III. Modéré

IV. Assez animé

V. Presque lent, dans un sentiment intime

VI. Vif

VII. Moins vif

VIII. Lent

(approximately 15 minutes)

Gershwin Arrangements

A foggy day in London town

They’re writing songs of love, but not for me

(approximately 10 minutes)

Program Notes

In preparing for this recital, I have been asking questions relating to each composer’s creative goals, inspirations, philosophies, performance approach, and cultural context. By considering these metrics, I endeavor to more deeply embody the spirit of each work. Listeners can explore the vast spectrum of music experience through the angle of each work, moving beyond just hearing notes and patterns. What follows is a collection of important information and my own observations relating to these questions. I hope these program notes will enhance your concert experience and even spur further curiosity. Thank you for joining me!

Ludwig van Beethoven – Piano Sonata in D Major, Op. 28

Feeling through Form

Beethoven composed the Sonata Op. 28 in 1801, a year in which he was in good spirits, having rare financial stability and even considering marriage. However, the following year, Beethoven would write from isolation the Heiligenstadt Testament, in which he confessed to his frustration and depression stemming from his hearing loss, fear of exposing his ailment, and the resulting disconnect he felt from society. Beethoven’s decision to ultimately persevere marked the start of his middle period, characterized by innovations to form and musical expression that led Europe into the Romantic period. In perhaps a moment of levity amidst this development, the Sonata Op. 28 represents a call to the elegance of the galant style. The music evokes the comforts and tranquility of the natural world that Beethoven valued. While not necessarily explicit in evoking imagery, the piece fits in a set of works considered “pastoral” in nature.

In the Allegro, the opening drone, triple meter, and use of primary chords create a warm energy and grounded momentum. The thematic manipulation and quick repetition in the development produce a feeling of strain and turbulence, which subsides when Beethoven reestablishes the opening texture. As is customary in sonata-allegro form, the recapitulation and final cadence stay in the tonic key, providing a feeling of content. However, the syncopation of the coda foreshadows the excitement of the final rondo.

The Andante, in the parallel key of d minor, strikes a darker tone. The theme undergoes variations and is set against a staccato bass accompaniment, adding to the scheming feel of the movement. The middle section returns to the parallel key of D Major, providing a momentary reprieve from the mystery of the piece’s unfolding. Moreover, these spritely chords and triplet arpeggios anticipate the character of the following Scherzo movement.

The Rondo’s rocking accompaniment and melody create a fun finale to the sonata. Beethoven’s use of syncopation and deliberate pauses preceding each return of the theme reveal a humorous and comical dialogue within the piece. As a resolution to the coda of the first movement, this movement ends with a speedy coda and resilient fortissimo cadence.

Beethoven commands mood and drama through a focused attention to musical events and form. In my approach, I try to clearly understand the structure of the piece and shape of each gesture to impart the feeling of the music, without obstructing the impact with excessive rubato or extraneous emoting.

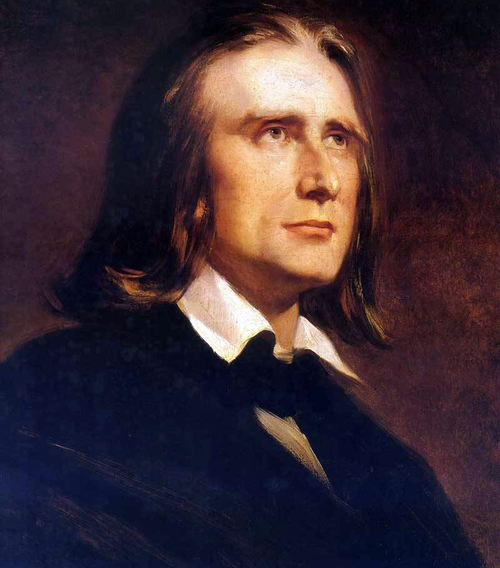

Franz Liszt – Two Concert Études, S. 145

Heightened Emotion

Liszt sought to create an impactful and engaging listening experience for audiences, harboring the room’s energy to feed into the creative process. Along with pianists like Clara Schumann (1819 – 1896), Liszt pioneered the solo piano concert format by opening the piano lid and angling the keyboard towards the listeners so they could appreciate the full range of timbres, colors and sound effects of the instrument, which at the time was the closest in resonance and power to the modern grand piano. In addition to original works, he performed arrangements and transcriptions of other composers’ work to promote an appreciation of a full gamut of musical experience and tradition. In teaching, Liszt underscored the study of theory and encouraged a holistic approach to technique that focused on freedom in music making and keyboard playing. Through expanded forms, thematic transformation and use of an improvisational style in playing and filling in textures, Liszt crafted exciting musical experiences rich in imagery and fantastical settings.

In Waldesrauschen (Forest Murmurs), the opening ostinato permeates the piece to create a shimmering layer of wind like resonance. Within this atmosphere, Liszt presents the theme and counter theme in different registers and key areas to help the listeners visualize and explore their surroundings, including the swaying of the trees and creaking of branches. The variety in dynamics, colors and intensity levels contributes further to the life of this soundworld.

In Gnomenreigen (Dance of the Gnomes), the quick staccato broken chords in f-sharp minor represent the dancing and plotting of gnomes. This leads to a recurring melodic idea in the relative major, surrounded by spinning arpeggio figures. The middle interlude features a winding and repetitious bass line that leads into the final melodic section and coda. While virtuosic in the use of arpeggios and passagework, the sound retains a delicate refinement, proportionate in scope to that of the characters and story world.

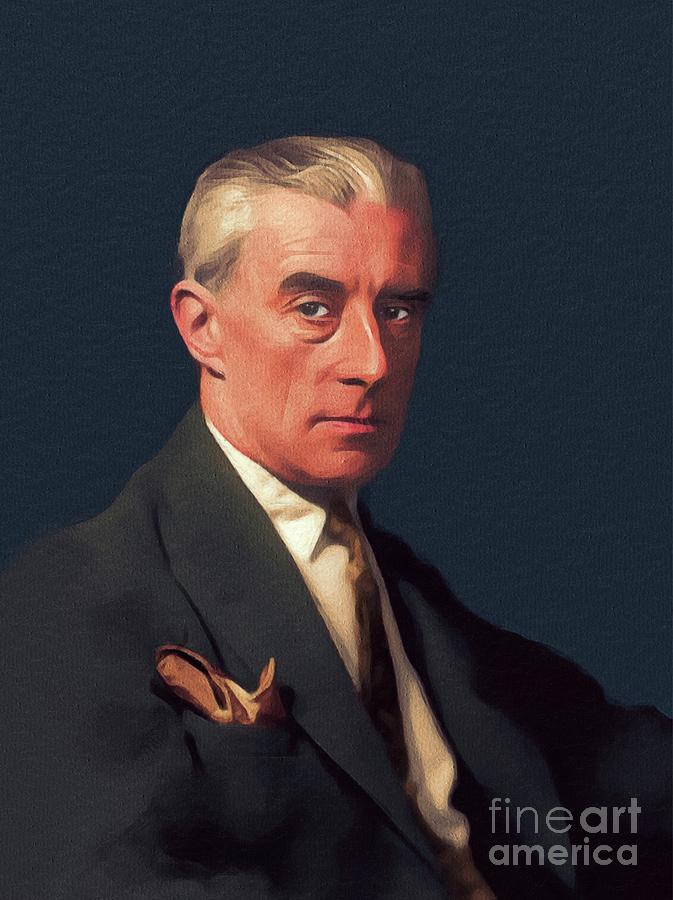

Maurice Ravel – Valses nobles et sentimentales

Color and Precision

Ravel composed the Valses nobles et sentimentales in 1911 to commemorate Schubert’s set of waltzes by the same name. As a composer, Ravel was very meticulous in communicating how his music was to be performed. He felt that the performer’s job was not to interpret his music, but simply to play. This strictness in adhering to the score may have been a response to performers at the turn of the 20th century who Ravel felt over-romanticized works. While Ravel can be considered an impressionistic composer due to his unique tonal language and harmonies, his attention to form and precise timing is neoclassical. So, while the listener may form an impression from works of this style, it is the pianist’s job to exercise precision in preparation and performance.

Drawing from recordings of Schubert waltzes, I strive to establish a feeling of the triple time and flow in each movement. I also work to bring out the colors and energy of each section by listening to the voicing of chords and resonance of notes while carefully rehearsing the choreography of pedaling. I also referred to the orchestral version which Ravel composed for the ballet Adelaide (1912), to better understand the color palette and waltz energy.

Michael Finnissy – Gershwin Arrangements

Nostalgia and Sensitivity

Finnissy takes inspiration from a variety of genres and traditions, exploring music making and found material in new settings. In his arranging of music, he explains, “it’s not the point to reveal what’s there already,” in other words, a resetting of material for the piano. Instead, Finnissy approaches arranging as a chance for new discovery, composing with others’ material as if it were his own. Finnissy’s body of work is diverse, including music considered “new complexity” due to its dense counterpoint and demanding rhythms, like his English Country Tunes (1977), as well as Renaissance style motets and music that considers the sonority of single melodic lines. In his Gershwin Arrangements, Finnissy preserves the general form and melody of iconic Gershwin songs while experimenting with new sound quality, tonality and sentiment.

In A foggy day in London town, the slower sections and rallentando evoke feelings of melodrama and moments of serious contemplation. When the tempo picks up, the narrator’s thought goes elsewhere with a carefree attitude. They’re writing songs of love, but not for me is marked “Quite slowly, sadly and tenderly.” The unmetered flow of the music and falling shape of the accompaniment figures in the verse sections contribute to the narrator’s wandering thought and abandoning of hope. In both pieces, the narrator is speaking with the same intensity of the original song setting through Finnissy’s unique compositional palette and writing, with moments of in and out of focus in sound. This helps the listener feel nostalgia for the original work while also enjoying a new listening sensation.