Performed Live at

Boston University College of Fine Arts, Marshall Room, Boston, MA.

Friday, September 23, 2022, 6:30 pm

Please join me for a tour through the ages – from Renaissance England to Classical Austria, to late-Romantic Russia, and finishing with a tribute to American Folk Music!

This program supports my partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) degree from Boston University and the College of Fine Arts.

Walsingham Variations

Theme + 29 Variations

(approximately 16 minutes)

Sonata in A Major, D. 664

I – Allegro moderato

II – Andante

III – Allegro

(approximately 15 minutes)

Sonata No. 5, Op. 53

One continuous sonata form movement

(approximately 13 minutes)

“In the Bottoms” Suite

IV. Barcarolle (Morning)

V. Juba (Dance)

(approximately 8 minutes)

Program Notes

This program includes works that have been personally eye-opening. As I am approaching the end of my formal studies, I wanted to choose major works by composers I still had not developed a strong understanding of. The more confident I grew learning the notes, the greater a role I felt the understanding of time periods, composers’ ideas and influences played on making this music speak as it was intended. I continuously discover new details and build a deeper appreciation for these pieces through my ongoing study, guidance of my teacher and advice of my peers. Most importantly, it is a reminder to celebrate this music and the chance to perform it for new audiences, who continue to give it life. What follows is a collection of key takeaways I feel speak to the core of what each work represents. I hope these notes will enhance your concert experience and even spur further curiosity. Thank you for joining me!

John Bull – Walsingham Variations

Keywords: Variety, Mood, Touch Types

Composed probably between 1596 and 1607

After receiving his doctoral degree in 1592 from Cambridge, Renaissance composer John Bull was one of the first faculty appointed to Gresham University in 1596 under the recommendation of Queen Elizabeth I. It is there he is believed to have composed the set of variations on a theme known as Walsingham, shown below:

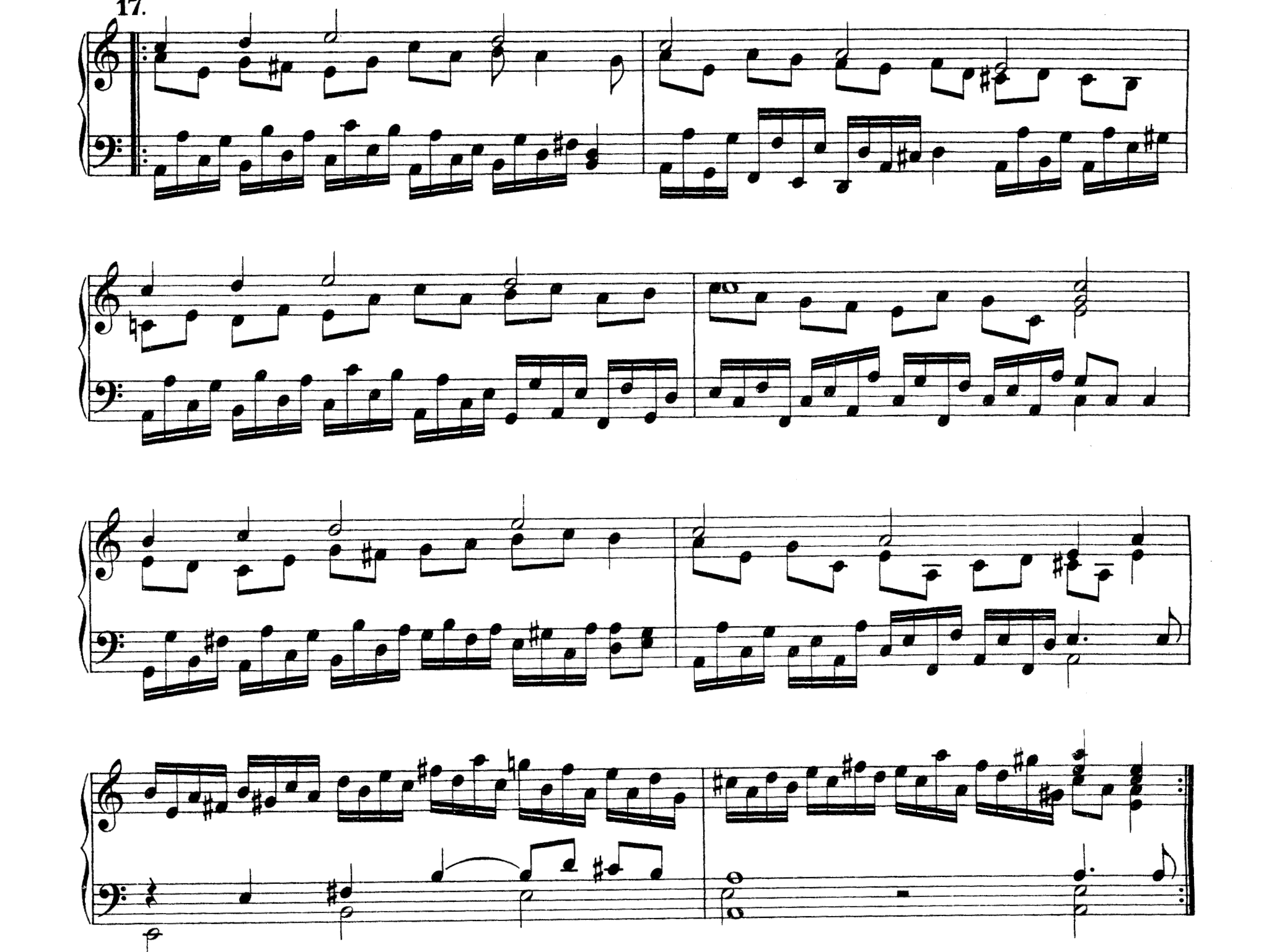

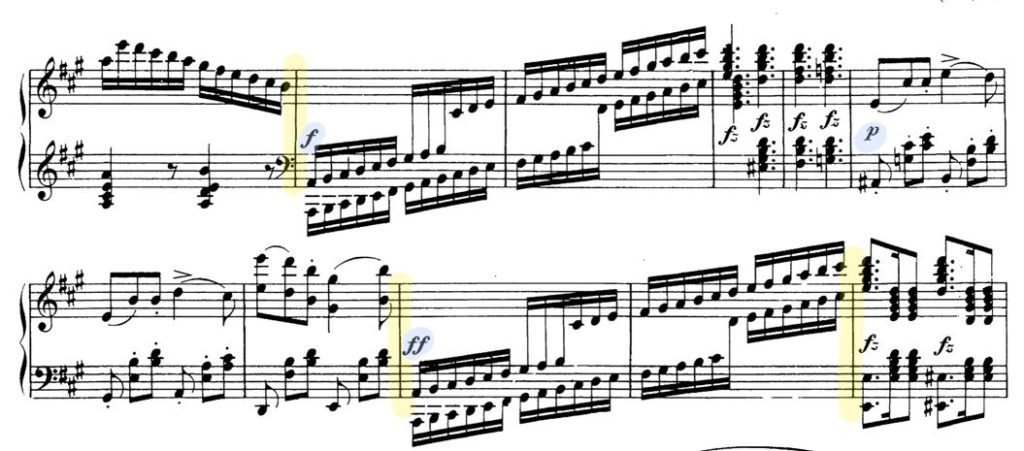

Bull uses the same melody and harmonic progression for each of his 30 variations. Herein lies the challenge as a pianist – since the variations are so similar in their sound and occur in close succession (each is only eight measures long) it is particularly important to find ways of distinguishing each one.

Because this piece was written for a virginal, an early plucked instrument, there are no articulation or dynamic markings in the score. However, a performer at the time could use several tricks to elicit different moods and give the illusion of varying dynamics. A variation with a higher volume of notes would naturally seem louder, and vice versa. A modern piano can accentuate these differences. The performer can also change tempos suddenly between two variations to capture a different intensity level or build gradually through successive variations. A modern piano also has more versatility in assigning touch types to the plethora of rhythmic motifs within variations, further distinguishing the feel and character of each.

It is up to the modern pianist to decide what range of experimentation fits within a stylistic interpretation. Composers up through the Baroque era believed that emotions existed as fixed states, and certain music could evoke each in a listener. As such, I have tried to choose a consistent tempo and articulation for each individual variation. Furthermore, I have tried to avoid using crescendo or decrescendo within variations, which the virginal could not do. I instead terrace the dynamics which means to change the dynamic level at a specific point like a repetition of a motif or new variation.

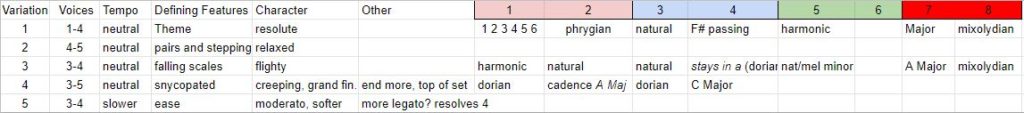

Finally, I approached memory by gradually building up sets of variations to form a more cohesive whole. I identified subsets of four to five variations that I could rehearse with attention to details and with continuity between variations. Then I created three large sections on the way to performing the entire piece. The chart below shows some of my reference notes for a group of variations:

This piece is improvisatory in the sense that Bull is experimenting with how to present the same material in many ways. Therefore, I believe it is important to be open to new ways of hearing and playing any given variation and even trying to ornament with spontaneity. After all, musicians performing in the Renaissance period were appreciated for their ability to entertain and also build community in social settings.

Franz Schubert – Sonata in A Major, D. 664

Keywords: Melody, Contrasts, Warmth

Composed in 1819

Schubert was known for crafting beautiful melodies, with Franz Liszt even declaring him “the most poetic musician who ever lived.” He wrote over 600 songs, known as lieder. By the time the Sonata in A Major, D.664 was composed, Schubert had already established himself as an innovative song writer. His favorite poetry was by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, of which Schubert set over 70 works. In 1815, Schubert wrote over 200 songs in total. Audiences were fascinated by Schubert’s more active use of the piano and clever harmonies, as well as his new approach to through-composing certain songs to better tell the story. One source notes –

Of course, to contemporary listeners who have become accustomed to the formlessness and colorful harmonies of works by Liszt, Strauss, or Debussy for instance, Schubert’s grand departure from strophic form may not shock or disturb. But Schubert’s innovations within the realm of Lieder were no less novel than Beethoven’s in symphonic music.

Gleason, Michaela. (2019). Cohesion and Conflict: Schubert, Goethe and the Creative Forces at Play in Song Study.

Completed in 1819 when he was only 22, Schubert dedicated this sonata to a pianist and singer named Josephine von Koller who also performed many of his lieder. Scholars believe the piece was inspired by the serenity Schubert felt in the Austrian mountainside where he was on vacation at the time.

Each of the three movements has a peaceful and warm melody. Within the melodic line, Schubert explores changes in harmony, especially using the parallel Major and minor, subito (sudden) dynamics, and register shifts, creating different colors and moments of both excitement and introspection. For these surprises, the sonata remains overall a joyful and benevolent piece and is even the shortest of all his sonatas, signally a time of comfort and positivity in Schubert’s tragically short and often troubled life.

Alexander Scriabin – Sonata No. 5, Op. 53

Keywords: Maximalist Sonority, Spontaneity, Immersion, Mysticism

Composed in 1907

Alexander Scriabin’s Sonata No. 5 is an explosion of sound and sonority. The accompanying poem reads –

I call you to life, O mysterious forces!

Drowned in the obscure depths

Of the creative spirit, timid

Shadows of life, to you I bring audacity!

— Alexander Scriabin

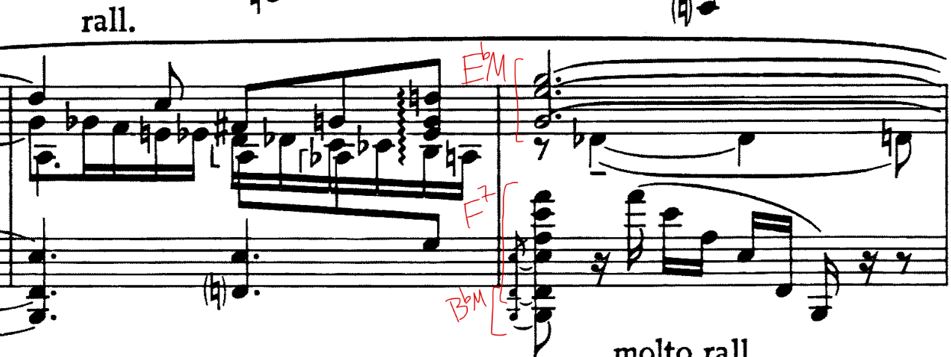

Interestingly, this piece is in a single movement sonata form. Scriabin uses this continuous form to greater immerse the listener. He maximizes each section of the sonata with multiple themes derived from similar intervals and rhythms as well as rich polyharmony, often stacking three harmonies at once, yielding amazing sonorities. So often, Scriabin creates small and large scale harmonic motion in which we hear chords resolving to each other in the short term but also realize that Scriabin is creating an even larger harmonic progression through the aggregate of these local sections, spanning an entire page.

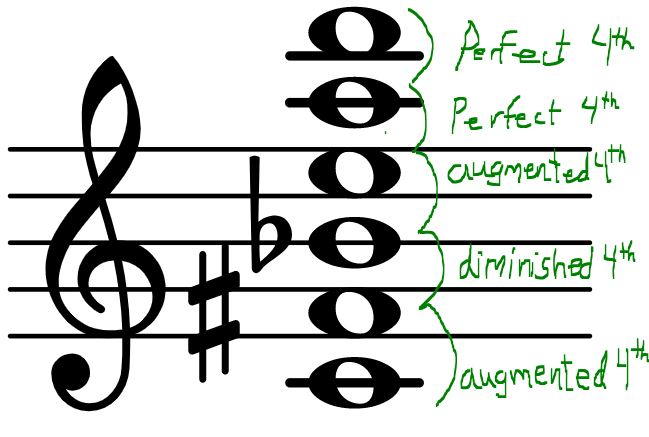

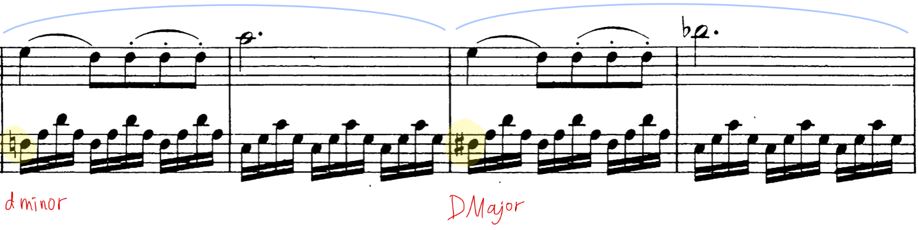

These sonorities were important to Scriabin, who had synesthesia, meaning he could see colors through sound. In fact, one sonority first heard in Sonata No. 5 in different permeations is the Mystic chord, made from a series of fourths intervals, seen below.

Can you spot the Mystic chord intervals in the chord below?

The sonata is packed full of content and overflowing with sonority which creates an immersive and sometimes confronting listening experience. The music both pulls an audience in with what feels like pools of gravity while breaking away unpredictably. It is a testament to Scriabin’s aural imagination and ingenuity.

Robert Nathaniel Dett

Barcarolle and Juba from “In The Bottoms” Suite

Keywords: Americana, Tradition, Character Pieces

Composed in 1913

Robert Nathaniel Dett, born in Canada and later living in the United States, was an esteemed musician, scholar and choir director. He received his bachelor’s degree and an honorary doctorate from Oberlin as well as a master’s degree from Eastman, where the Sibley Library preserves many of his manuscripts. He also studied at Harvard University and at the American Conservatory with pedagogue Nadia Boulanger.

In 1926, he became the music director at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, and as conductor, he skyrocketed the choir to national prestige with critically acclaimed performances at New York’s Carnegie Hall and Boston’s Symphony Hall, among others. In 1930, the Hampton Choir toured seven countries and performed for President Hoover at the White House.

In addition to composing vocal and keyboard works, Dett was a skilled arranger of music and created two collections of “Negro Spirituals.” Furthermore, Dett wrote extensively on the history of African-American music and its modern performance, for which he received numerous awards from major universities.

His set of character pieces from 1913, entitled “In the Bottoms,” are “impressions of moods or scenes” from slave life in the river bottoms in the South. The term barcarolle refers to a morning river boat ride and juba, as Dett describes, refers to slaves “stamping on the ground with the foot and following it with two staccato pats of the hands in two-four time.”

We have this wonderful store of folk music—the melodies of an enslaved people… But this store will be of no value unless we utilize it, unless we treat it in such manner that it can be presented in choral form, in lyric and operatic works, in concertos and suites and salon music—unless our musical architects take the rough timber of Negro themes and fashion from it music which will prove that we, too, have national feelings and characteristics, as have the European peoples whose forms we have zealously followed for so long.

— R. Nathaniel Dett

Robert Nathaniel Dett’s contributions to composition and commitment to ethnomusicology prove him to be one of the most important and forward looking 20th century American voices.

Thank You to Boston University, to my friends, family and my teacher, Linda Jiorle-Nagy, for your keen mentorship and unwavering support.